End the twin sieges of Gaza

Israel is keeping supplies out — but Egypt is keeping refugees in.

The situation of civilians in Gaza is untenable and about to get even worse. Families are packed in crowded and unsanitary conditions into a tiny area around Rafah, cut off from health care, and, according to credible reports, already dying of starvation.

Now Israel is preparing to invade Rafah as it continues its response to the Oct. 7 massacre by Hamas terrorists. The Israel Defense Forces is reportedly preparing to move Rafah’s civilians, most of whom have already been displaced at least once, to areas it has already conquered. But these places lie in ruins, with no infrastructure to support civilians and little prospect of better supply delivery.

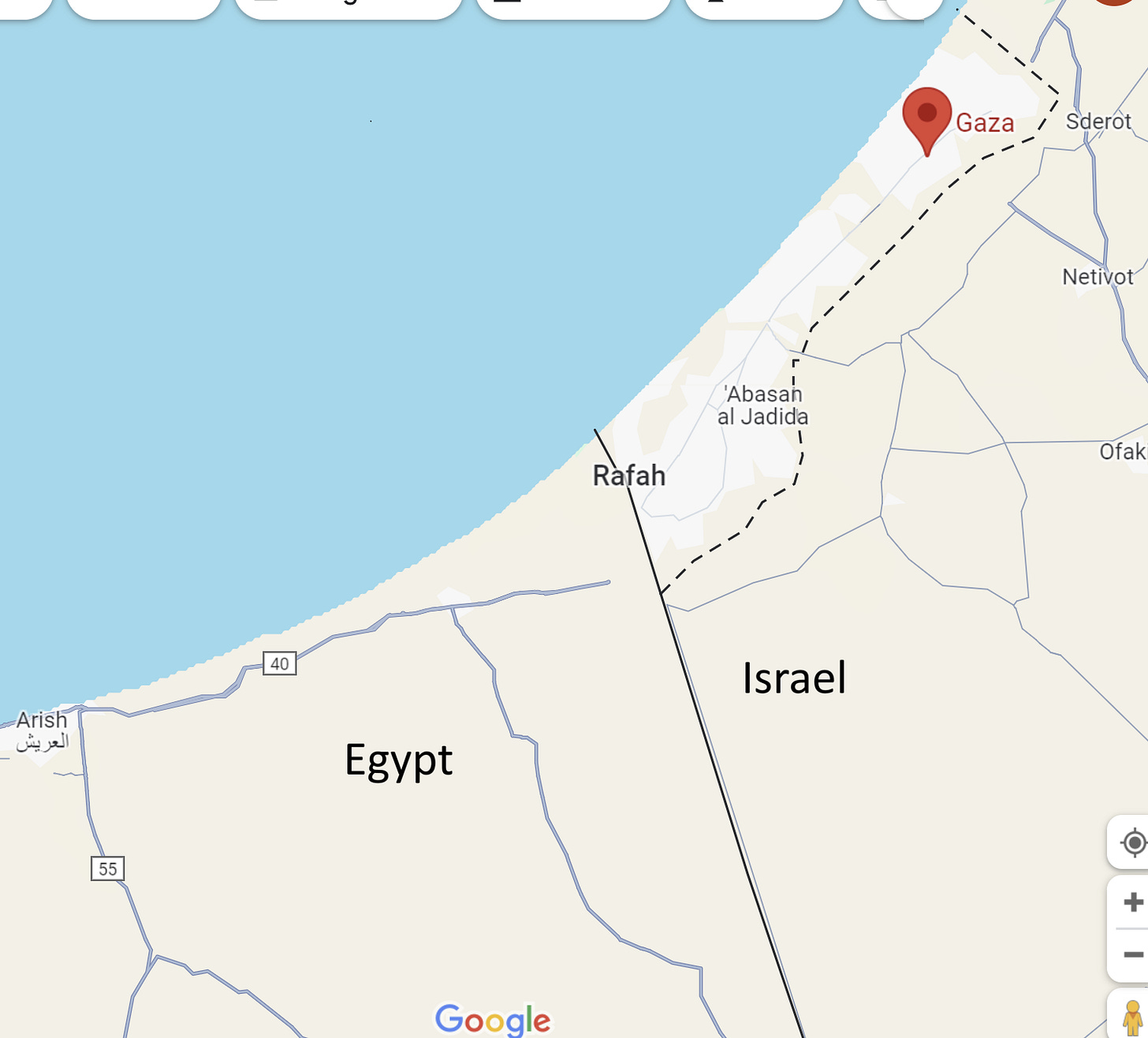

The world must act now to stave off worst-case scenarios, and it must apply common sense. The first step is to recognize that Gaza today is under two sieges, one from Israel and the other from Egypt. As we all know, Israel is preventing most goods from coming in — more on that later. But the stunningly obvious flipside that no responsible decisionmakers seem willing to examine is that Egypt is preventing refugees from coming out.

Exile, choice, and obligation

If Gaza is riven with fighting and depleted of supplies, a rather obvious solution is to let people go to the place next door where there is ample food and no fighting. Instead, Egypt’s ruler, Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi, has sent tanks to the border to ensure Gazans don’t get any ideas about leaving — and the international community hasn’t made a peep.

Egypt has sought to shut down any talk of receiving Gazans with the claim that this would make it complicit in Palestinians’ permanent expulsion from their land. It is true that hard-right ministers in Benjamin Netanyahu’s government have aired despicable fantasies of such a permanent exile. But these fantasies are well outside the Israeli mainstream, and as we will see, any Egyptian opening of the border would presuppose ironclad guarantees that Gazans’ exile would be temporary.

In any case, if there is any uncertainty in the matter, it seems to me that the choice whether to risk exile should be up to the people in the war zone — not the people who sympathize with their cause at a distance. Instead of preemptively accusing Israel of a sinister plot for “ethnic cleansing,” advocates for Palestine would do well to push for an option to evacuate to Egypt, lean on Western governments to secure guarantees from Israeli leaders, and strengthen Israel’s mainstream forces rather than condemning them as complicit in evil.

Meanwhile, many Palestine advocates who have backed South Africa’s legal campaign against Israel overlook the fact that Egypt’s sealing of its border is a grievous violation of international law.[1] “Pushbacks” of asylees at the border defy both the individual right to seek asylum and the principle that states cannot expel bona fide refugees back to places of danger, enshrined in global accords that Egypt has ratified. In fact, Egypt is a signatory to an African regional convention that explicitly recognizes the right to asylum for people fleeing war and prohibits “rejection at the frontier.”

To its credit, Egypt has lived up to these responsibilities on its other borders, hosting some half a million refugees, according to UNHCR — including people who have fled the civil war in Sudan, on its southern border. So what makes the Gaza war different?[2]

Egyptian fears, Israeli fears

Al-Sisi is sweeping aside these obligations out of fear that hosting hundreds of thousands of Gazan refugees could strain his economy and destabilize Egypt. These are indeed legitimate problems. The economic difficulty could be addressed with a massive infusion of international aid, but there is a thornier security concern. Terrorist groups could use Palestinian population centers to recruit and to stage operations. Extremists could reignite an insurgency that Egypt has struggled to put down in its Sinai Peninsula; they could also fire at Israel from Egyptian territory, raising the prospect of another dangerous front in the war. And Hamas is an offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood, which Sisi himself deposed and repressed in the wake of Egypt’s short-lived revolution.

Those problems, however, are no more vexing than the ones now facing Israel. Jerusalem is justly concerned that aid deliveries will be used to smuggle in arms and that Hamas will continue its practice of stealing food, fuel, and medicine intended for civilians. That would allow its fighters to remain indefinitely in their tunnels and bog the IDF down in endless warfare that would only prolong suffering on both sides. Indeed, the IDF reportedly assesses that 60 percent of aid deliveries are being diverted to Hamas.

At the same time, it also appears that Benjamin Netanyahu’s government views humanitarian aid as a bargaining chip for the return of Israeli hostages. That is the sentiment being voiced by many of the protesters who have sought to block deliveries from the Israeli side of the border. I understand this impulse, especially since most of the aid goes directly to the enemy. But even allowing for Hamas theft, my best reading of the situation is that aid deliveries likely do save large numbers of innocent Palestinian lives, and therefore they must continue.[3]

Deadly hypocrisy

It would be both morally disastrous and strategically self-defeating for Israel, Arab nations, and the West to permit mass starvation or disease to take hold in Gaza. But these problems will never be solved if all the players persist in ignoring them. Egypt must open its borders and prepare to host Gazans. (It is encouraging that Egypt now appears to be preparing some kind of buffer zone just across from Rafah, but it’s unclear whether this is designed to be a containment area in case Palestinians break through or preparation for an actual welcome.)

Israel must think urgently and creatively about delivering more aid to civilians in the strip. Israeli leaders at the highest levels must also to publicly reassure Gazans that they intend to let them return home, and rebuff the extremists who suggest otherwise. Netanyahu several weeks ago released a video to that effect, but the message needs to be repeated — and not just in English. (The best message of all, of course, would be if Netanyahu purged the extremist Itamar Ben Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich from his government.)

Both countries must work together to screen people leaving the strip (ensuring there are no hostages or significant Hamas figures among them) and to agree how to handle security threats from extremists operating in Egypt. Finally, both must begin serious planning for the post-war governance and rebuilding of Gaza, in which Egypt will have to take on more responsibility than it has in the past. The United States, Europe, and Arab nations must pressure Israel and Egypt to take these steps, provide the necessary financial support, and ensure accountability.

The evacuation of some number of Gazans to Egypt would hardly be unprecedented. Poland is currently hosting 1.6 million Ukrainian refugees. Refugees from the Syrian civil war were welcomed to Turkey (3.5 million as of 2022), Lebanon (815,000), Jordan (661,000), Germany (523,000), and many other countries including Egypt.

This embrace of Ukrainian and Syrian refugees fleeing the aggression of dictators has been celebrated across the world as an act of charity. But when Israel defends itself from attack, it is taken for granted that Palestinian civilians must remain in the crossfire — and any suggestion of evacuating them is denounced as complicity with some evil design. This hypocrisy is a terrible indictment not only of how we see Israelis, but also of how we see Palestinians.

[1] The right to asylum is guaranteed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which Egypt has ratified. The “principle of non-refoulement” holds that asylum seekers cannot be expelled to the place where they would be endangered, and Egypt has ratified the 1951 refugee convention enshrining it. The right to asylum narrowly understood only extends to cases in which people are being specifically targeted on the basis of religion, ethnicity, political opinion, etc., but it can be argued based on other principles that insecurity generated by war also qualifies. In this case there is no argument, however, because Egypt has explicitly committed to that position by ratifying the 1969 OAU Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa. The same convention specifically rejects “pushbacks,” noting: “No person shall be subjected by a Member State to measures such as rejection at the frontier … which would compel him to return to or remain in a territory where his life, physical integrity or liberty would be threatened” by war.

[2] This AP story claims that Egypt hosts 9 million refugees, but I haven’t been able to confirm this much larger number with any official sources.

[3] Israeli officials have declared that there is “enough food” in Gaza, and figures from the military unit responsible for this issue indicate that 15 bakeries are supplying 2 million pitas a day. I am deeply skeptical of the UN’s role in Gaza and, as discussed elsewhere, find that most allegations that Israel has engaged in “indiscriminate bombing” are badly misinformed or issued in bad faith. But when aid groups in unison declare that famine is looming — including the WFP, run by the widow of John McCain — and when fighting has virtually shut down the economy, I find it hard to believe there is no problem. This hardly means Israel is deliberating starving the civilian population of Gaza — as noted above, supply aid means resupplying Hamas, and fighting cannot simply be toggled on and off to allow deliveries. But there certainly is a huge problem here we must grapple with.